Examining the Exam Room

Be Sure to Look for Symptoms in the Waiting Area

As an integral part of the diagnostic process, medical practitioners have relied on visual cues throughout history. Even today, the amount of information that can be gathered through technologically-unaided observation is astounding. As it turns out, the same kind of criteria applied to a primary care waiting room can tell us a great deal about the health of a physician practice in general and the condition of the exam room in particular.

For example, the most basic observation can reveal that waiting rooms are often full of disgruntled people, some of whom have taken to posting videos documenting long waits – which takes negative word-of-mouth to a whole new level. It gets even worse as we occasionally hear of patients who bill their physicians for loss of productive time. While those kind of extreme measures remain rare, the fact is that wait times perceived as being overly long correlate with everything from patient satisfaction and medical compliance to return show rate and overall attitude toward clinicians and staff.

But while the waiting area manifests the symptoms, the problem often lies in the exam room, the very place that patients are anxiously waiting to enter.

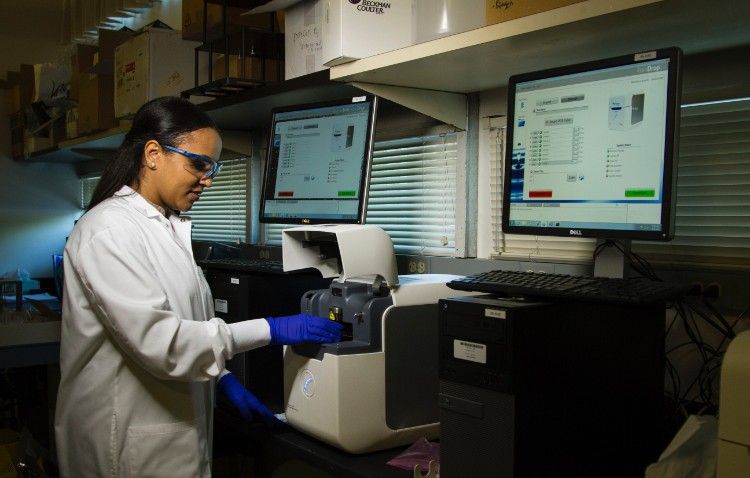

Behind those closed doors you’ll still find doctors looking at a computer screen instead of the patient, creating a scenario that neither party considers to be satisfactory. And because the practitioners may be slowed down by the quirks or intricacies of the particular EMR platform, more critical minutes are spent accomplishing less for the people in the exam room – while those in the waiting room … wait.

The typical doctor-centric exam room process isn’t doing the physician any good, either, resulting as it often does in longer days, more work taken home and financial liabilities related to reduced capacity.

The good news is that a “healthier” exam room and, subsequently, an improved waiting room experience can be achieved with some restructuring of the exam room process. And it starts with a specially-trained assistant, generally an RN or protocol-backed MA taking over the data entry portion for the current episode of care while also serving as an information resource for preventive care.

There are a lot of reasons why waiting rooms back up, ranging from the complexity of care and multiple health issues to patients running late, but we’re kidding ourselves if we don’t recognize that wait times are an important issue that will only get worse as coverage continues to expand.

And we’re doing our patients — and ourselves — a disservice if we don’t look for solutions in the exam room.